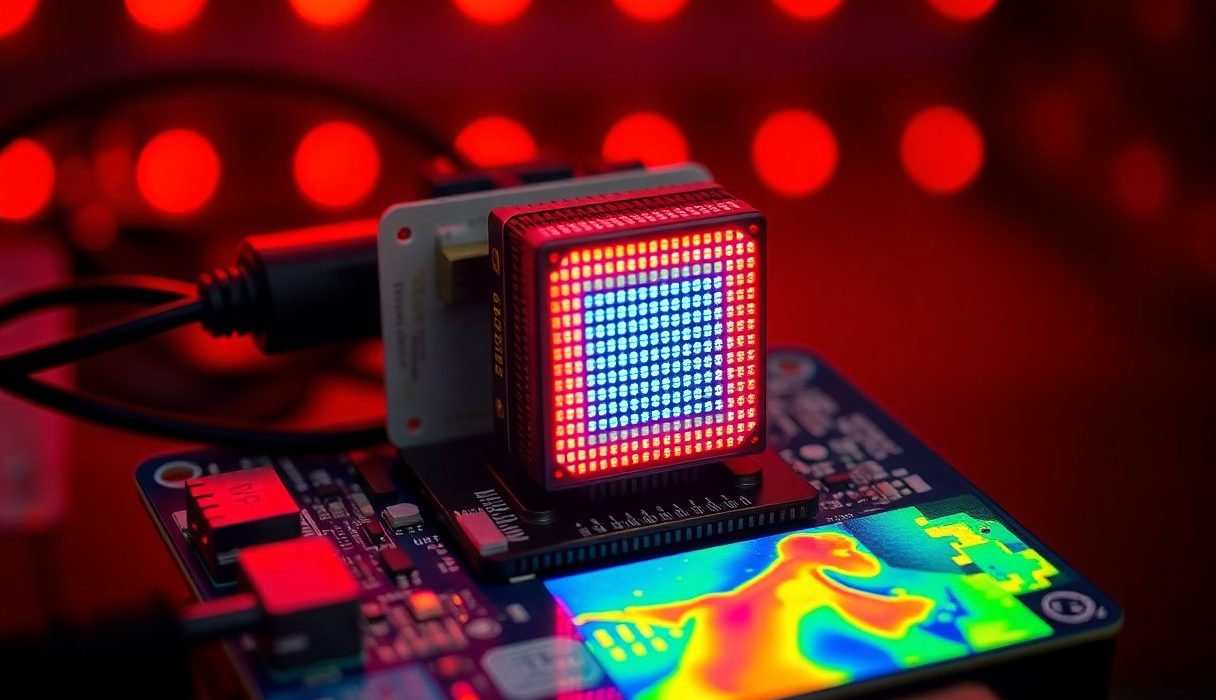

You can deploy infrared array sensors to visualize temperature patterns across a scene, giving your system real-time thermal imaging and high sensitivity for tasks ranging from equipment inspection to medical screening. Their pixelated detectors enable precise, non-contact temperature measurements, help detect early fires and overheating hazards, and support automated monitoring that reduces downtime and improves safety.

Types of Infrared Array Sensors

| Type | Key characteristics |

| Active Infrared Sensors | Use a controlled IR illumination source (LED, laser) paired with an array detector; common bands include 850-1550 nm, useful for depth sensing and short- to medium-range detection (typical structured-light depth cameras: 0.5-5 m; automotive LiDAR: up to 200-250 m). |

| Passive Infrared Sensors | Detect emitted thermal radiation without illumination; split between uncooled arrays (microbolometer, LWIR 8-14 µm, NETD ~30-60 mK for 640×480 sensors at 30 Hz) and cooled photon detectors (InSb/HgCdTe, MWIR/LWIR, NETD <20 mK, frame rates >100 Hz). |

| Common applications |

|

| Performance metrics | Pixel pitch (7-17 µm typical), resolution (80×60 to 1280×1024+), NETD, frame rate (30-120 Hz common), response time (ms to µs depending on detector type), and power/eye-safety constraints for active systems. |

Active Infrared Sensors

When you work with active arrays you exploit a known illumination pattern or pulsed source so the array measures reflected energy or time-of-flight; examples include structured-light modules (Kinect-style systems using ~850 nm emitters with effective ranges of 0.5-4.5 m and depth resolution of a few millimeters) and pulsed LiDAR systems using 905 nm lasers for automotive ranges >150 m. Manufacturers frequently pair CMOS-based detectors or SPAD arrays for timing-SPAD arrays now achieve timing jitter near 60 ps, enabling sub-decimeter ranging when optics and signal processing are optimized.

Since you control the illumination, active sensors deliver depth in total darkness and perform well against low-contrast scenes, but you must balance benefits against trade-offs: eye-safety limits on emitted power at common wavelengths, potential detectability by adversaries using IR imagers, and added system power consumption (structured-light modules typically draw 1-5 W; automotive LiDARs may draw tens of watts). Practical deployments often pair active arrays with IR band-pass filters and algorithms that mitigate reflections and ambient sunlight interference.

Passive Infrared Sensors

You rely on passive arrays to map true thermal emission, which makes them preferred for temperature measurement and long-term surveillance. In uncooled microbolometer arrays, expect NETD in the 30-60 mK range for 640×480 sensors with 17 µm pixels at 30 Hz; those are used for building inspection and firefighting drones where weight and power matter. Conversely, cooled photon detectors such as HgCdTe deliver NETD <20 mK and high frame rates, which you see in aerospace and scientific platforms where cryocoolers and size/weight/power penalties are acceptable.

Deployment examples show the differences clearly: a 640×480 microbolometer with a 25 mm lens resolves human-sized thermal contrasts at tens to a few hundred meters depending on background clutter, while a cooled 320×256 MWIR camera can detect smaller thermal targets at greater standoff distances and support tracking at >100 Hz. You should weigh NETD, spectral band (MWIR vs LWIR), and operational environment when selecting a passive array for imaging versus quantitative thermometry.

For motion-detection use cases you often choose simple pyroelectric PIR arrays or dual-element sensors that give reliable binary or low-resolution outputs at very low cost and power; typical commercial PIR modules detect human motion across 5-12 m with angular coverage of 90-120° and form the backbone of alarm systems and automated lighting where you care more about event detection than calibrated temperature maps.

Thou must prioritize NETD, wavelength band, detector architecture, and operational constraints to ensure your chosen array meets detection-range, response-time, and cost targets.

Tips for Choosing Infrared Array Sensors

When you compare sensors, prioritize measurable specs: sensor resolution (common choices are 8×8, 32×32, 80×60, and 160×120), NETD (noise-equivalent temperature difference – typical uncooled values are 50 mK down to 30 mK for high-sensitivity models), and frame rate (9 Hz is common due to export limits; 30-60 Hz is used for dynamic tracking). Consider lens options and field of view (FOV) because a 60° lens on a 32×32 array gives very different spatial resolution at 5 m than a 12° lens, and check whether the sensor requires onboard calibration or an external blackbody for the accuracy you need (industrial temperature control often demands ±0.5°C or better, while medical screening targets ±0.3°C under controlled conditions).

- Resolution

- NETD

- Frame rate

- Field of view / optics

- Interface (I2C, SPI, USB)

- Calibration method

- Environmental rating (IP, operating range)

- Power consumption / cost

This prioritization will help you narrow down vendors and modules that meet both your performance targets and system constraints.

Assessing Application Needs

You should map the sensor’s spatial and thermal resolution to the task: use 8×8 or 32×32 arrays for presence, people-counting, and low-detail occupancy sensing at ranges under 5 m, while selecting 80×60 or higher for object recognition, hotspot localization, or short-range thermography where you need millimeter-level detail at 1-5 m. For fever screening or any medical-related detection, specify an accuracy target (for example, ±0.3°C) and include a calibration plan – often a NIST-traceable blackbody or ambient reference is necessary to reach that performance in the field.

You also need to define latency and processing location: if you require real-time tracking at >30 Hz, ensure the sensor and host MCU/GPU can sustain the data rate and algorithmic load; for edge deployments with limited power, choose low-power modules with onboard aggregation or a reduced frame rate (9-15 Hz) and implement smart event-triggering to save energy and bandwidth.

Considering Environmental Factors

Account for the installation environment: if the sensor will operate in outdoor or industrial settings, verify the operating temperature range (many uncooled modules specify −20°C to +70°C; extended models go to −40°C/+85°C), IP rating (IP65-IP68 for washdown or submerged use), and tolerance to condensation or steam. You should also check whether scene obstructions (window glass, polycarbonate) attenuate LWIR – typical window transmission for 8-14 µm is near 0% for soda-lime glass, while Germanium and chalcogenide materials transmit strongly but add cost and weight.

- Operating temperature range

- IP / sealing

- Condensation / dew prevention

- Window material (Ge, ZnSe, chalcogenide)

- Vibration / shock tolerance

- EMI / nearby heat sources

Any protective measures (heaters, purge systems, or IP-rated housings) should be specified early in the design to avoid rework.

For deployments where condensation, dust, or splashing are likely, design mechanical and thermal mitigation up front: a heated germanium window held 10-20°C above ambient dew point prevents fogging, and a small purge flow (for example, 0.2-1 L/min of dry air) can keep optics clean in dusty industrial lines. In coastal or chemical environments choose housings with sacrificial coatings or stainless-steel enclosures and verify that your chosen lens material (Germanium is common for 8-14 µm, while Silicon works for 3-5 µm) suits both the spectral band and chemical exposure.

- Heated window

- Purge / dry-air flow

- Window material selection

- Corrosion-resistant housing

Any decision on housings, windows, and thermal management will directly affect sensor lifetime and measurement accuracy.

Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing Thermal Detection

Implementation Overview

| Step | Details |

|---|---|

| Planning & requirements | Define detection range and target size (e.g., detect a 0.5 m object at 5 m). Choose resolution accordingly: MLX90640 (32×24) for coarse mapping, FLIR Lepton 3.5 (160×120) for finer features. |

| Hardware selection | Match sensor FOV and lens: 60° FOV covers ~5.8 m width at 5 m distance. Check supply: many arrays require 3.3 V and draw 50-200 mA depending on model. |

| Mounting & optics | Mount between 1-3 m for room monitoring; use screw mounts or VESA adapters and ensure optical window is clean. Consider protective housings with IR-transparent windows (e.g., germanium or chalcogenide glass) for outdoor use. |

| Power & wiring | Use decoupling caps near the module, keep I2C lines under 1 m or use differential drivers for longer runs. Protect against ESD and reverse polarity with diodes or dedicated PMIC. |

| Connectivity & data | Stream at required frame rate: 8-16 FPS for people tracking, 30+ FPS for fast dynamics. Choose I2C for simple integration, SPI or MIPI for higher throughput. |

| Initial testing | Allow warm-up 3-5 minutes for sensor thermal stabilization. Run a live feed to verify no saturated pixels and check background subtraction under expected lighting and thermal conditions. |

| Calibration & correction | Perform emissivity setting (human skin ~0.98), two-point gain/offset calibration using a blackbody or calibrated thermometer, and apply non-uniformity correction (NUC) per-pixel. |

| Maintenance | Schedule recalibration every 6-12 months or after housing changes; log sensor health and error counts for proactive replacement. |

Installing the Sensor

You should position the sensor so that its optical axis covers the intended detection zone without obstructions; for human-temperature monitoring place the module 1.5-2.5 m above the floor and angle it to cover the expected transit path, which typically yields reliable readings up to 5-7 m with mid-resolution arrays. Pay attention to field-of-view math: a 60° FOV subtends ~5.8 m at 5 m distance, so choose lens and mount to match target size and distance.

During physical installation, protect the module from heat sources and direct sunlight because solar loading and nearby heaters can saturate and bias readings. Use a gasketed enclosure with an IR-transparent window outdoors, and ensure power wiring includes a decoupling capacitor and reverse-polarity protection; improper wiring can cause permanent damage in many sensor modules, so verify polarity and grounding before applying power.

Calibrating for Optimal Performance

You should start calibration after warm-up (allow 3-5 minutes) and with a stable ambient reference; perform a two-point calibration using a room-temperature reference (around 20-25 °C) and a heated blackbody at a second point (for example 40-50 °C) to compute gain and offset per pixel. For arrays, execute a non-uniformity correction (NUC): capture multiple frames of a uniform target and compute per-pixel offsets to reduce fixed-pattern noise so you can approach accuracies of ±0.5 °C under controlled conditions.

In software, implement emissivity correction and ambient temperature compensation-set emissivity to ~0.98 for human skin or adjust to the material being monitored. Also apply temporal filtering (e.g., a 3-5 frame moving average) to suppress frame-to-frame noise while preserving responsiveness; for safety-critical detections, use shorter filters and flag transient spikes for manual review.

For best long-term accuracy, you should validate against a NIST-traceable blackbody when possible and document calibration constants; field deployments often need periodic recalibration (every 6-12 months) or after significant environmental changes, and automated drift checks (compare a small on-board reference or ambient sensor) help maintain performance without frequent manual intervention.

Factors Influencing Sensor Performance

Performance hinges on both sensor design and the environment you deploy it in. Key variables interact in ways that change detection thresholds, false alarm rates, and the spatial and thermal fidelity you can achieve:

- NETD – sets the smallest temperature difference you can detect; values ≤50 mK are desirable for fine discrimination like fever screening.

- Temperature range – determines dynamic range and risk of saturation when viewing very hot targets or sub-freezing scenes.

- Emissivity – low-emissivity surfaces (polished metals) produce weaker signals and increase measurement error unless compensated.

- Distance / field of view (FOV) – controls spatial resolution per pixel (IFOV) and signal dilution with range.

- Optics & aperture – focal length and lens transmission affect IFOV and throughput; materials like germanium are common in LWIR optics.

- Pixel size & resolution – larger pixels collect more photons (better SNR) but reduce image detail for a fixed array size.

- Frame rate & integration time – trade off temporal resolution vs. per-frame SNR; longer integration improves sensitivity but can blur moving targets.

- Calibration & drift – sensor offset and gain change with ambient; periodic calibration stabilizes absolute temperature accuracy.

Practical deployments show trade-offs: a 320×240 microbolometer with a NETD of 40 mK will detect small temperature contrasts at close range, but if you push it to view a furnace at 500 °C without a high-temperature calibration and an appropriate lens you’ll hit saturation and lose measurement fidelity. For long standoffs you often need narrower FOV optics and larger apertures to maintain useful spatial resolution and signal strength. Recognizing how these variables combine lets you prioritize hardware and configuration for your application.

Temperature Range

You must distinguish between the sensor’s operating ambient range and the measurable scene temperature span: many uncooled microbolometer modules are specified for ambient use roughly from -20 °C to +60 °C, while the scene temperatures they can estimate (with appropriate optics and calibration) often extend from below freezing up to several hundred degrees Celsius. For example, a factory inspection camera calibrated for 0-400 °C will use different gain settings and filtering than a wellness screening unit tuned around 30-45 °C.

Temperature Range – Key Effects

| Specification | Impact / Considerations |

|---|---|

| Operating ambient | Affects electronics reliability and drift; may require heating or cooling for extreme climates. |

| Measurable scene range | Determines dynamic range and whether saturation occurs on hot targets; affects calibration curve. |

| NETD vs span | Wider spans can degrade effective NETD for a given gain setting; close-range medical use favors low NETD. |

| Calibration frequency | High-duty or high-temperature environments require more frequent recalibration to maintain accuracy. |

| Application examples | Fever detection: narrow span 30-45 °C; industrial thermography: 0-800 °C with appropriate optics and emissivity correction. |

When you configure sensors, consider multi-range approaches: use automatic gain control or switchable filters for very hot targets, and implement regular in-field calibration using blackbody references where you need absolute accuracy. If you ignore dynamic range limits, you risk clipped readings or inflated errors on low-emissivity surfaces.

Distance and Field of View

Your choice of focal length and sensor IFOV directly sets the spatial resolution at target distance: IFOV (radians) ≈ pixel pitch / focal length, and spatial resolution on target ≈ distance × IFOV. For instance, with an IFOV of 1 mrad, each pixel covers ~5 cm at 50 m; with 0.5 mrad that drops to ~2.5 cm. That arithmetic guides lens selection-wide FOV lenses cover more area but reduce per-pixel detail, while narrow-angle telephoto optics concentrate energy per pixel and improve detection at range.

Atmospheric effects become significant as distance increases: humidity, dust, or steam attenuate LWIR energy and can produce false positives or reduced contrast beyond a few tens of meters in poor conditions. You can mitigate this by increasing aperture, using shorter optical paths, selecting higher-resolution arrays, or choosing wavelengths within the 8-14 µm atmospheric window for longest practical range.

In a concrete example, a 640×480 sensor with a 25 mm lens and a 17 µm pixel pitch gives IFOV ≈ 0.68 mrad (17e-6 / 0.025). At 20 m that corresponds to approximately 13.6 mm per pixel, so if you need to resolve 5 mm features you must either move closer, increase focal length, or use a higher-resolution detector; these are the practical levers you adjust when optimizing detection performance.

Pros and Cons of Infrared Array Sensors

Pros and Cons Summary

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Passive thermal detection – you can image in total darkness without illumination. | Atmospheric effects – fog, rain and steam can attenuate LWIR and reduce range/contrast. |

| High thermal sensitivity: many uncooled microbolometers achieve NETD around 30-100 mK; cooled detectors can reach <20 mK. | Spatial resolution limits – common modules (e.g., 80×60, 320×240) provide coarse imagery versus visible cameras. |

| Low-power, compact modules are available (Lepton-class modules ~0.5-2 W), easing integration into battery-powered systems. | Cooled detectors add significant cost and power: system costs often exceed $10,000 and require cryocoolers. |

| Fast frame rates for dynamic monitoring – many arrays support 30-120 Hz, suitable for motion tracking and process control. | Require non-uniformity correction (NUC) and periodic calibration to avoid drift and fixed-pattern noise. |

| Non-contact temperature measurement enables predictive maintenance and building diagnostics without shutdowns. | Emissivity dependence – temperature readings can be off by several °C if emissivity or reflected backgrounds are misestimated. |

| Ruggedization options and enclosures (IP65-IP67) let you deploy sensors outdoors and in industrial environments. | Optics and aperture requirements increase size/weight for long-range or high-resolution applications. |

| Proven safety and security applications (fire detection, perimeter monitoring) with many off-the-shelf algorithms. | Susceptible to saturation/blooming when viewing very hot sources (flames, molten metal), reducing diagnostic detail. |

| Compatibility with fusion systems – you can combine IR arrays with visible/RGB or LiDAR to improve situational awareness. | Regulatory/privacy concerns in some jurisdictions when thermal imaging is used for surveillance. |

Advantages

You gain the ability to see temperature contrasts that are invisible to other sensors: microbolometer arrays let you detect sub-0.1°C differentials in many practical setups, which is why manufacturers use them for bearing-temperature monitoring and electrical-panel inspections. In field deployments you can use compact modules (80×60 to 320×240 resolution) to implement continuous condition monitoring that, in case studies, has reduced unplanned downtime by tens of percent when integrated into maintenance programs.

Your system benefits from passive operation and low-light performance; because infrared arrays do not need active illumination they work for night surveillance, search-and-rescue, and process control. You can also scale from low-cost consumer modules (hundreds of dollars) to high-end cooled focal plane arrays used in research and defense, and select frame rates from 30 Hz up to 120 Hz+ for real-time tracking or high-speed thermal analysis.

Disadvantages

You must contend with trade-offs: uncooled sensors give you affordability and low power but at the expense of spatial resolution and somewhat higher NETD, while cooled sensors deliver superior sensitivity and speed but impose much higher cost, power draw, and maintenance (cryocooler lifetime, vibration, and routine servicing). In practice this means system-level decisions – optics size, thermal stabilization, and maintenance budgets – often dominate total project cost.

Operationally, your measurements can be misled by emissivity variations and atmospheric conditions; surfaces with low emissivity or reflective backgrounds produce erroneous apparent temperatures, and fog/steam can eliminate contrast over short ranges. Additionally, sensor artifacts like fixed-pattern noise and drift force you to implement NUC routines and periodic reference-based calibration to keep absolute temperature accuracy within acceptable bounds.

Mitigation is possible but adds complexity: you can reduce emissivity errors by using reference tiles, apply radiometric calibration tables, fuse visible imagery for scene context, or choose larger-aperture optics to improve spatial resolution – however each mitigation increases cost, weight, or computational requirements, so you should balance those against your performance targets and operational environment.

Applications of Thermal Detection

You encounter infrared array sensors deployed across sectors where visible-light inspection fails: maintenance shops, building envelopes, emergency response, and smart homes. Typical uncooled microbolometer modules range from roughly 80×60 to 320×240 pixels with noise-equivalent temperature differences (NETD) commonly between 50-100 mK (0.05-0.1 °C)

In practice, these arrays turn surface temperature maps into operational decisions: condition-based maintenance algorithms take thermal inputs to schedule repairs, building-energy audits quantify heat loss room-by-room, and security systems use thermal motion signatures for 24/7 detection. Field reports indicate inspection throughput can increase by 4-10× when you switch from manual, visual checks to drone- or trolley-mounted thermal surveys, and that early hotspot detection typically prevents escalation into costly downtime or fire risk. When you inspect electrical switchgear, a thermal array reveals hotspots that often precede arc faults; spotting a component running 10-30 °C above surrounding hardware lets you plan an outage before failure. Manufacturing lines use line-scan thermal arrays to monitor soldering, plastic molding and glass tempering; you can detect a 5-10 °C deviation across a conveyorized part in real time and trigger an automated reject to avoid large batch losses. Vibration-bearing or motor monitoring benefits from correlating thermal rise with RPM and vibration spectra: if a motor bearing shows a steady temperature increase of >20 °C over baseline across several shifts, you should flag it for lubrication or replacement. Utilities and petrochemical plants integrate thermal cameras into routine thermographic inspections to comply with standards such as NFPA‑70B and to reduce manual access to high-voltage or confined spaces, thereby lowering safety risk and inspection time. You see thermal sensors migrating into smartphones, IoT devices and home appliances for practical tasks: energy audits that pinpoint window and insulation losses, baby monitors that track skin-surface temperature, and cooking aids that measure pan hotspots. Add-on modules and embedded boards typically offer resolutions from 80×60 up to 160×120 pixels in cost-sensitive devices, with higher-end embedded products reaching 320×240 for better identification and range. Integration choices matter: a lower-NETD module gives you finer temperature discrimination for medical-adjacent uses, while higher frame rates (9-30 Hz) improve tracking for gesture or occupancy detection. Beware that reflective surfaces and emissivity differences produce false readings, so you must calibrate for emissivity or fuse thermal data with visible cameras and ambient sensors to avoid misinterpretation-this is especially important when thermal data drives safety-related actions. In consumer products the balance is between cost, power and performance: modules can cost from roughly $50 to several hundred dollars depending on resolution and NETD, and you should design for on-device processing to limit bandwidth and preserve privacy; at the same time you can leverage simple ML classifiers on the edge to distinguish people from pets and reduce false alarms while keeping sensitive thermal imagery local. Hence you can rely on infrared array sensors to turn thermal radiation into actionable spatial temperature data, enabling non-contact detection of heat, movement, and thermal patterns across a scene. Your choice of sensor-defined by resolution, sensitivity, frame rate and optics-determines how finely you can resolve hotspots, track transient events and integrate thermal data with control or alerting systems, while onboard processing and calibration ensure accurate, repeatable measurements in real-world conditions. When you evaluate or deploy these sensors, balance performance against cost, environmental robustness and integration complexity to meet your application goals, whether for safety, predictive maintenance, healthcare or security. With improvements in detector technology and algorithmic analysis, your thermal detection capabilities will become more precise and versatile, allowing you to detect smaller anomalies faster and to extract richer information from thermal scenes. Industrial Uses

Consumer Electronics

Summing up